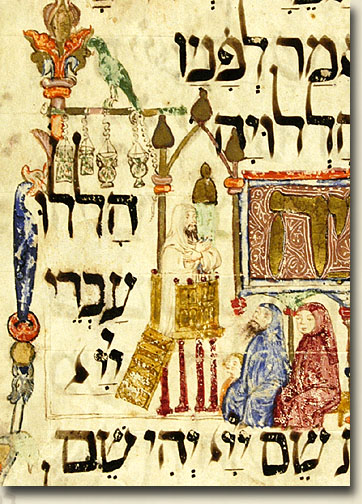

The lamps that appear in the fine panel, depicting the interior of a synagogue in the text, are indicative of a certain Middle Eastern connection (fol. 42r). This panel illustrates the morning prayer, which forms part of the Pesach ritual. 205 (This practice – no longer followed – consisted of reciting the haggadah in the synagogue for the benefit of those who were unskilled in reciting it.) 206 These lamps must have been quite widespread in contemporary Catalonia because they appear not only in other places of our manuscript (fols 1v; 6r) but in other Haggadahs of Catalonian origin too. 207 In connection with these lamps it may be noted that they are characteristic of Cairene mosques of the Mamluk period – the best known among them are perhaps the splendid specimens decorating the Mosque of Sultan Hasan.

One must note that, in Egypt, the mosques at night were lit by lamps of glass or bronze. The former, at the best period, were of polychrome enamelled glass made in Syria. The art of making such lamps appears to have developed about A. D. 1250 and to have died out at the very beginning of the fifteenth century, probably owing to the disaster of 1401, when Damascus was captured by Timur, or Tamerlane, who led its architects and craftsmen away captive to embellish his capital Samarkand. Only about a hundred and fifty of these enamelled glass lamps have survived and about three quarters of them are in the possession of the Museum of Arab Art [=Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo today]. 208

In the Mahzor produced in Germany, perhaps in Heilbronn, between 1370 and 1400 (MS Kaufmann A 387), in connection with one of the prayers of the Day of Atonement the artist depicted the scene when the male figure, coming from the sanctuary in accordance with Leviticus 16:22 and traditional imagination, casts the scapegoat from the cliff into the abyss, to Azazel, who appears in our illustration as a horned and clawed mountain demon or devil. 209

205 For a detailed description of

the scene see Sed-Rajna:

The Kaufmann Haggadah. Budapest 1990. 13. Cf. also

Müller – von Schlosser:

Bilderhaggaden 1898. 197 [ad p. 72]. Narkiss

– Sed-Rajna 1988. Kaufmann Haggadah. Card No. 43.

205 For a detailed description of

the scene see Sed-Rajna:

The Kaufmann Haggadah. Budapest 1990. 13. Cf. also

Müller – von Schlosser:

Bilderhaggaden 1898. 197 [ad p. 72]. Narkiss

– Sed-Rajna 1988. Kaufmann Haggadah. Card No. 43.

206 Joseph

Gutmann: The illuminated

medieval Passover haggadah: investigations and research problems. In:

Studies in Bibliography and Booklore 7 (1965) 18 [of the

offprint].

207 Similar lamps can be seen in the

Sarajevo Haggadah, in the Haggadahs of the British Library shelf-marks

Or. 2737 (fol. 20v) and 2884 (fol. 17v) – all three Haggadahs are of

Spanish origin. Eugen Werber:

The Sarajevo Haggadah. Sarajevo 1988. fol. 34r [plates],

fol. 31v [text]. Narkiss 1982. II. 21 [Fig. 81].

Müller

– von Schlosser: Die

Haggadah 1898. 321.

Ibid. Tafelband.

Fol. 34. Müller –

von Schlosser: Bilderhaggaden 1898. 104-105 [fol.

17v], Tafel VI, Fig. 1. In the latter place we can see the interior of a

synagogue wholly reminiscent of ours (MS Brit. Mus. Or. 2884, fol. 17v).

G. Margoliouth's

description, according to which it shows “the head of the family in a

sort of «Mimbar», or pulpit” is probably false although the Hebrew

caption says so itself. Müller

– von Schlosser:

Bilderhaggaden 1898. 110.

Munkácsi's effort at solving this riddle remains unsuccessful.

Ernest [=Ernő] Munkácsi:

Ancient and medieval synagogues in representations of the fine arts.

In: Jubilee volume in honour of Prof. Bernhard Heller on the occasion

of his seventieth birthday. Ed. by Alexander Scheiber. Budapest

1941. 246-247. Vid. also Narkiss 1982. I 75 [ad fol. 17v], II. 59 [fig.

187]. A similar interior can also be seen in the

Catalonian Haggadah Add. 14761 in the British Library. Ibid. I. 83 [fol.

65v], II. 78 [fig. 241]. Cf.

Gutmann 1965. 18 [of

the offprint.

208 Keppel Archibald Cameron

Creswell: Architectural

note. In: Count Patrice

de

Zogheb: Our home in

Cairo. With an architectural note by Professor K. A. C.

Creswell. Alexandria [1941]

27-28. On the enamelled glass lamps see Max

Herz: Le Musée National

du Caire. In: Gazette des Beaux-Arts. Ser. 3, v. 28 (1902) 497-505.

Id.: [Gouvernement

Égyptien. Comité de conservation des monuments de l'art arabe.]

Catalogue raisonné des monuments exposés dans le Musée National de l'Art

Arabe précédé d'un aperçu de l'histoire de l'architecture et des arts

industriels en Égypte. Deuxième édition. Cairo 1906. 297-338.

Id.: [Egyptian

Government. Commission for the Preservation of Monuments of Arab Art.].

A descriptive catalogue of the objects exhibited in the National Museum

of Arab Art preceded by a historical sketch of the architecture and

industrial arts of the Arabs in Egypt. Second edition. Transl. by G.

Foster

Smith. Cairo 1907. 275-312.

According to Diez the

technique of the production of enamelled glass lamps passed from Iraq to

Syria, then to Egypt and from there to Venice. Ernst

Diez: Die Kunst der

islamischen Völker. [2nd edition?] Wildpark-Potsdam [no date (after

1926)]. 191. Esin Atil:

Renaissance of Islam. Art of the Mamluks. Washington, D.C. 1981.

118-124, esp. 120-121. These lamps – like other Mamluk glass products –

were imitated in Europe at the end of the 19th century. Ibid. 123. A

shabbat-lamp of this type originating from Damascus, with Hebrew

inscription, is preserved in the Jewish Museum in London.

Sed-Rajna 1976. 126.

(According to the caption the lamp is made of glass but it seems rather

to be made of silver.)

209

Kaufmann 1898. 270. Narkiss

– Sed-Rajna 1988. The Heilbronn Mahzor. Card No. 25. On Azazel

see Encyclopaedia Judaica. Jerusalem – New York 1971-1972. III.

999-1000. Bibel-Lexikon 1981. 155-156 (s.v. Azazel).