3.5.

The Genizah of Cairo

3.5.

The Genizah of Cairo

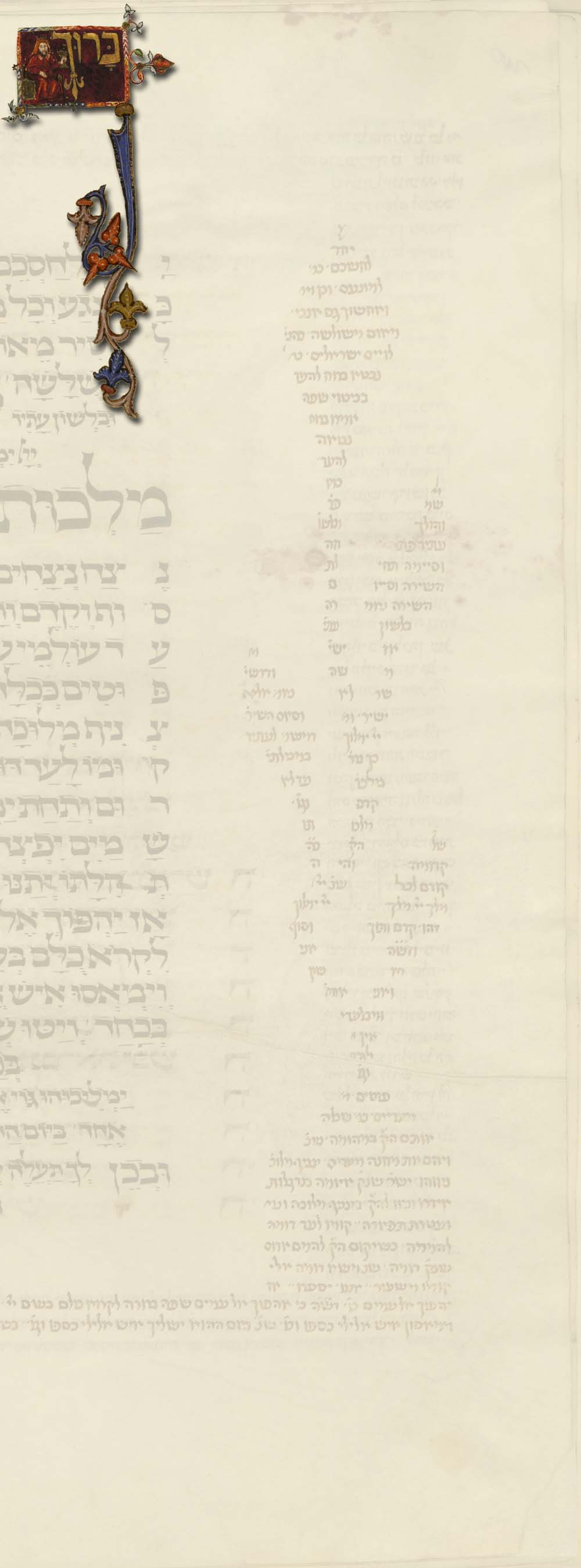

The shelf-marks MSS Kaufmann A 592, A

593 and A 594 indicate a collection of fragments from the Cairo Genizah, 210

approximately six-hundred fragments. A catalogue of them is soon to be published

within the framework of a joint project of our Oriental Collection and the

Institute of Microfilmed Hebrew Manuscripts in the Jewish National and

University Library in Jerusalem. The description of the items is now nearing its

completion by Ezra Chwat.

The shelf-marks MSS Kaufmann A 592, A

593 and A 594 indicate a collection of fragments from the Cairo Genizah, 210

approximately six-hundred fragments. A catalogue of them is soon to be published

within the framework of a joint project of our Oriental Collection and the

Institute of Microfilmed Hebrew Manuscripts in the Jewish National and

University Library in Jerusalem. The description of the items is now nearing its

completion by Ezra Chwat.

We do not know how Kaufmann acquired his fragments, he never wrote on this subject. 211 One of his students, Izidor Goldberger, tells us – and he may have heard this only from Kaufmann – that

He was among those who first wiped off the pitch-black dust of a thousand years from the papyrus leaves of the Cairo Genizah. And it was only the careless Hungarian connection that handed over these precious items to the University of Cambridge. The scholar's only consolation for the lost treasures was to admit that they went to a good place. 212

It is worth noting that

Goldberger is referring to a

Hungarian connection, while Kaufmann

uses the expression “Oriental friend” in his letter published by

Schmelzer in his contribution to

the present volume. Was he perhaps a Hungarian Jew?

Scheiber succeeded in tracing

Kaufmann’s letters to

Schechter in the possession of a

dealer in London in 1975, where some clues to the solution of this question

might have been found, but had no time to read them. 213

Scheiber acquired xerocopies of

fifteen letters of Schechter

written in London and Cambridge between 24 November 1889 and 15 December 1898

and sent to Kaufmann to various

addresses in Budapest, Kojetein, Heringsdorf (Ostsee), Seebad Kolberg and

Karlsbad ([Hotel] Belle Alliance). From these it appears that a very friendly

relation existed between these two outstanding scholars.

Schechter regularly informed

Kaufmann of confidential matters.

When following the death of Schiller-Szinessy

the post of Reader in Rabbinic Literature became vacant at Cambridge University

and Schechter applied for it in 1890, he requested

Kaufmann for a letter of

recommendation, a “testimonial,” to attest his scholarly qualities and

achievements and recommend him to this post.

Kaufmann seems to have fulfilled

this request because somewhat later

Schechter thanked him most devotedly for the kind and appreciative

“testimonial.” Schechter supplied

Kaufmann also with data concerning

the family Gomperz. After the

discovery of the Genizah, Schechter

repeatedly informed Kaufmann of the

richness of the material. Kaufmann

seems to have requested Schechter

to send him fragments – probably for inspection – but

Schechter declined this request on the ground that the

Trustees would not agree to a dispatch of the fragments overseas. Now and then

Schechter requested copies of

passages from Kaufmann’s Mishnah

codex. There were also many complaints against Adolf

Neubauer, whom neither

Kaufmann nor

Schechter seemed to be particularly

fond of. 214

Both of them were very keen on that

Neubauer would not have the possibility of seeing the fragments from the

Genizah. Some letters are in the hand of the “secretary,” Mathilde S.

Schechter, Schechter’s

wife, who also wrote at least one very kind letter to

Kaufmann, whom he wished to get acquainted with so much

because she had heard so many good things about him from her husband. It is most

thrilling to read Schechter’s lines

on his progress in sifting the Genizah material at Cambridge. The reader is

reminded once again that no human being in this world is granted pure,

unadulterated happiness: going through the Genizah material

Schechter had to realize that a

considerable part was in Arabic, a language he was completely ignorant of. He

repeatedly complained to Kaufmann

that he did not understand a word of this portion of the Genizah and asked him

to go to Cambridge to help him.

Scheiber acquired xerocopies of

fifteen letters of Schechter

written in London and Cambridge between 24 November 1889 and 15 December 1898

and sent to Kaufmann to various

addresses in Budapest, Kojetein, Heringsdorf (Ostsee), Seebad Kolberg and

Karlsbad ([Hotel] Belle Alliance). From these it appears that a very friendly

relation existed between these two outstanding scholars.

Schechter regularly informed

Kaufmann of confidential matters.

When following the death of Schiller-Szinessy

the post of Reader in Rabbinic Literature became vacant at Cambridge University

and Schechter applied for it in 1890, he requested

Kaufmann for a letter of

recommendation, a “testimonial,” to attest his scholarly qualities and

achievements and recommend him to this post.

Kaufmann seems to have fulfilled

this request because somewhat later

Schechter thanked him most devotedly for the kind and appreciative

“testimonial.” Schechter supplied

Kaufmann also with data concerning

the family Gomperz. After the

discovery of the Genizah, Schechter

repeatedly informed Kaufmann of the

richness of the material. Kaufmann

seems to have requested Schechter

to send him fragments – probably for inspection – but

Schechter declined this request on the ground that the

Trustees would not agree to a dispatch of the fragments overseas. Now and then

Schechter requested copies of

passages from Kaufmann’s Mishnah

codex. There were also many complaints against Adolf

Neubauer, whom neither

Kaufmann nor

Schechter seemed to be particularly

fond of. 214

Both of them were very keen on that

Neubauer would not have the possibility of seeing the fragments from the

Genizah. Some letters are in the hand of the “secretary,” Mathilde S.

Schechter, Schechter’s

wife, who also wrote at least one very kind letter to

Kaufmann, whom he wished to get acquainted with so much

because she had heard so many good things about him from her husband. It is most

thrilling to read Schechter’s lines

on his progress in sifting the Genizah material at Cambridge. The reader is

reminded once again that no human being in this world is granted pure,

unadulterated happiness: going through the Genizah material

Schechter had to realize that a

considerable part was in Arabic, a language he was completely ignorant of. He

repeatedly complained to Kaufmann

that he did not understand a word of this portion of the Genizah and asked him

to go to Cambridge to help him.

Ludwig Blau recalled:

This treasure all but came to Budapest. The late David Kaufmann, professor at the Rabbinical Seminary, was negotiating for purchasing the complete geniza. He became deadly pale when he had learned that Schechter, who had travelled to Cairo for this purpose, had got it before him. 215

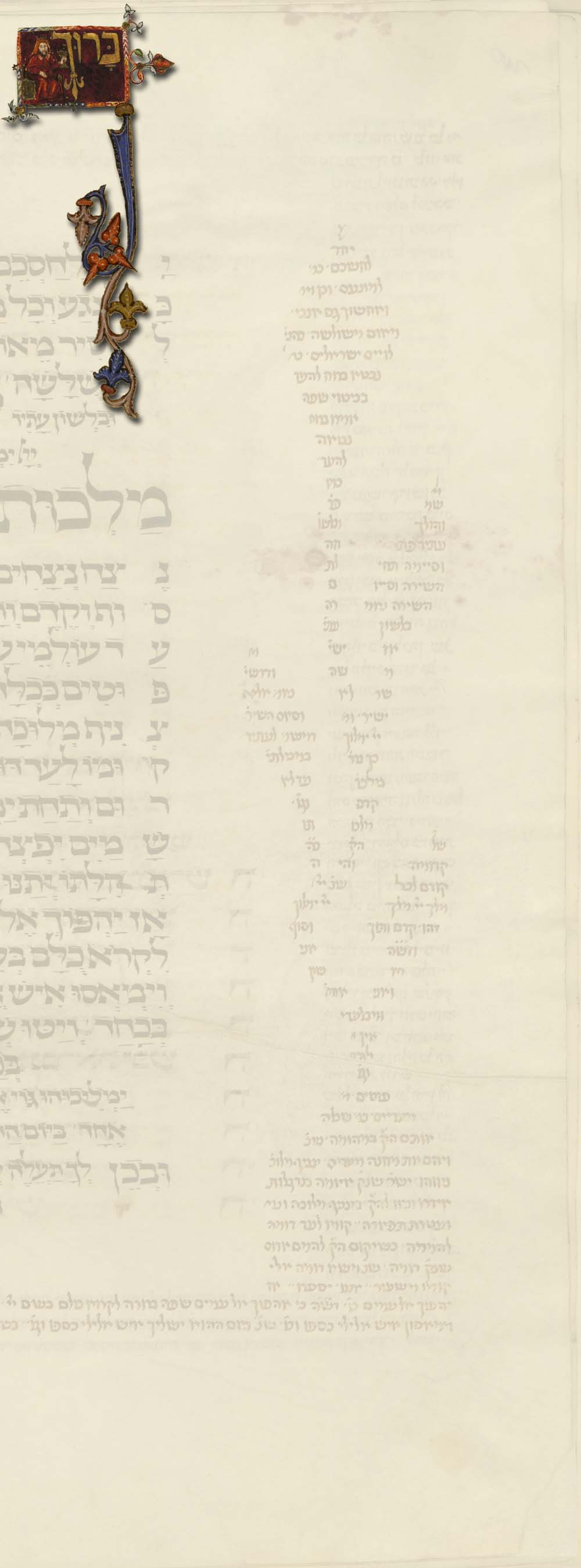

This item of information must also have come from Kaufmann. He also mentions this himself in a remarkable letter recently discovered and published in the present volume by Hermann I. Schmelzer of Sankt Gallen. Scheiber still saw a cardboard box with the inscription in Kaufmann’s hand: Aus der Genisa einer egyptischen Synagoge. Di[enstag]. 11. Dec. 1894. 216 This date precedes Schechter’s visit by two years.

Is it perhaps due to pure chance that the most important Genizah collection in the whole world is not kept in the Oriental Collection today?

210 See now Stefan C.

Reif: A Jewish archive

from Cairo. London 2000.

211

Scheiber Sándor [=Alexander

Scheiber]: A

Kaufmann-geniza kutatása és jelentősége. [=Research on the Kaufmann

Genizah and its importance.] In:

Scheiber Sándor:

Folklór és tárgytörténet. Budapest 1977-1984. III. 501-502.

Alexander Scheiber:

The Kaufmann-Genizah: Its importance for the world of scholarship.

In: Jubilee volume of the Oriental Collection 1951–1976. Papers

presented on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the Oriental

Collection of the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Ed.

by Éva Apor.

[Keleti Tanulmányok, 2]. Budapest 1978. 176-179.

212

Goldberger 1900. 19.

213

Scheiber 1977-1984. III.

501-502. Scheiber

1978. 176.

214 Cf.

Reif 2000. 74-78, 83, 240.

215

Blau Lajos [=Ludwig

Blau]: Fosztat városa,

Maimonides működésének színhelye. [=The city of Fustat, the stage of

Maimonides’ activities]. In: Magyar-Zsidó Szemle 1938. 57.

[Reprinted in:] Blau Lajos:

Zsidók és a világkultúra. [=Jews and world culture]. Ed. by János

Kőbányai. Budapest 1999.

331.

216 Alexander

Scheiber: Qetacim

hadašim mi-Sefer Talmuda rabba šel Yosef ben Yacaqob

ha-babli. In: Semitic studies in memory of Immanuel Löw. Ed.

by Alexander Scheiber.

Budapest 1947. 164 [Hebrew section].

Scheiber 1977-1984. III.

502. Scheiber 1978. 179.