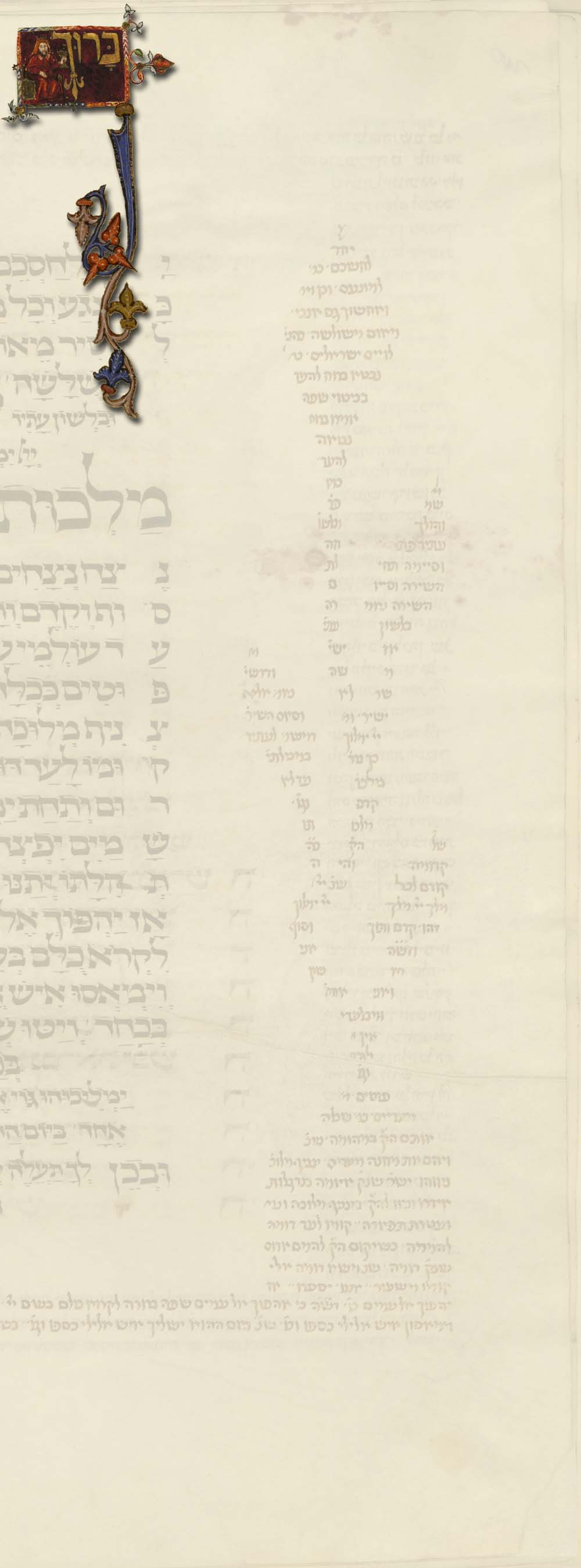

On account of their iconographical

interest and simple charm let us select some signs of the Zodiac – in this type

of Mahzor they illustrate two piyyuts by Eleazar Kalir (6th c.), the prayer for dew and rain on the

Day of Atonement. The types of representation of the signs of the Zodiac in our

manuscript closely correspond to similar representations in contemporary

Christian calendars, breviaries and psalters. 160

Within the framework of the religio-astrological interpretation of the cosmic

system, the Zodiac represents the signs of the night sky while the illustrations

of the months stand for the earth by representing the labours characteristic of

the given period of the year. 161

The most interesting and most enigmatic of all of them is without doubt the sign

of Gemini. Generally, the

representation of this sign ranges from a transformation of Castor and Pollux as

a caressing pair of a male and female to two armed knights embracing in a fight. 162

In our case we can see two

dog-headed figures facing each other holding an unidentifiable device with a

shaft in their hands (a mirror with a red frame? a shaft or stick with a red

plate? a flower?). 163

It also seems as if the figure on the right had a

On account of their iconographical

interest and simple charm let us select some signs of the Zodiac – in this type

of Mahzor they illustrate two piyyuts by Eleazar Kalir (6th c.), the prayer for dew and rain on the

Day of Atonement. The types of representation of the signs of the Zodiac in our

manuscript closely correspond to similar representations in contemporary

Christian calendars, breviaries and psalters. 160

Within the framework of the religio-astrological interpretation of the cosmic

system, the Zodiac represents the signs of the night sky while the illustrations

of the months stand for the earth by representing the labours characteristic of

the given period of the year. 161

The most interesting and most enigmatic of all of them is without doubt the sign

of Gemini. Generally, the

representation of this sign ranges from a transformation of Castor and Pollux as

a caressing pair of a male and female to two armed knights embracing in a fight. 162

In our case we can see two

dog-headed figures facing each other holding an unidentifiable device with a

shaft in their hands (a mirror with a red frame? a shaft or stick with a red

plate? a flower?). 163

It also seems as if the figure on the right had a

kerchief on its head,

suggesting that the figures are male and female. 164

Such a representation of Gemini is unknown elsewhere in Europe, and Gotthard

Strohmaier has succeeded in tracing

this motif to the Islamic world at the same time recognizing it also in one of

the enigmatic ornamentations of a mediaeval German altarcloth dating from the

end of the 13th century, the so-called Zehdenicker Altartuch, one of the

treasures of the Märkisches Museum in Berlin. 165

The problem requires further investigation. In the accompanying medallion, in

Müller's and

von Schlosser's view, the female figure can be taken to

represent the idealized love of mediaeval German courtly and knightly love, Frau

Minne, with crown and sceptre, sitting in the flowering branches of a tree and

holding a falcon on her left hand. Narkiss

and Sed-Rajna recognize in this figure the labour of hawking or the

flower-bearer characteristic of the month of Siwan. 166

In Sed-Rajna’s opinion the man is

wearing a crown. Perhaps rather a falconer's cap? In general, both motifs – the

falconer/hawking and man/woman with flowers – were common for April-May-June and

August. 167

Sed-Rajna stresses that the female

figure may hark back to an antique prototype, that of Rosalia, too, representing

the awakening of Nature. 168

The fantastic representation of Cancer, perhaps betraying Oriental influence, is

also remarkable: “a hybrid

animal composed of a wolf’s body and head, a griffon's paws and a fish for a

tail” 169 – this type of representation is unique to our manuscript, it cannot be found

anywhere else. Next to it we see a man digging the soil as the labour of the

month of Tammuz 170

– while the representation of

Scorpion as a tortoise should not

surprise us, because an illuminator living in the vicinity of Lake Constance at

the beginning of the 14th century may not have had the faintest idea what a real

scorpion looked like – the labour of the month of Marheshwan is the vine

harvest. 171

It may be noted in this context that the representation of Scorpion as a

tortoise among the signs of the Zodiac was common in contemporary Christian art,

too. 172

The combined sign of Aquarius and Capricorn radiates a certain rustic atmosphere

with the beautiful sweep (draw-well) and the kid quenching its thirst from the

bucket. Next to it we see in two medallions a sower and a peasant

“holding up a boot while warming his bare foot by the fire, above which hangs a

cauldron.” 173

The figure of a man warming himself by the fire was a widespread motif in the

representation of the winter months (December, January). 174

kerchief on its head,

suggesting that the figures are male and female. 164

Such a representation of Gemini is unknown elsewhere in Europe, and Gotthard

Strohmaier has succeeded in tracing

this motif to the Islamic world at the same time recognizing it also in one of

the enigmatic ornamentations of a mediaeval German altarcloth dating from the

end of the 13th century, the so-called Zehdenicker Altartuch, one of the

treasures of the Märkisches Museum in Berlin. 165

The problem requires further investigation. In the accompanying medallion, in

Müller's and

von Schlosser's view, the female figure can be taken to

represent the idealized love of mediaeval German courtly and knightly love, Frau

Minne, with crown and sceptre, sitting in the flowering branches of a tree and

holding a falcon on her left hand. Narkiss

and Sed-Rajna recognize in this figure the labour of hawking or the

flower-bearer characteristic of the month of Siwan. 166

In Sed-Rajna’s opinion the man is

wearing a crown. Perhaps rather a falconer's cap? In general, both motifs – the

falconer/hawking and man/woman with flowers – were common for April-May-June and

August. 167

Sed-Rajna stresses that the female

figure may hark back to an antique prototype, that of Rosalia, too, representing

the awakening of Nature. 168

The fantastic representation of Cancer, perhaps betraying Oriental influence, is

also remarkable: “a hybrid

animal composed of a wolf’s body and head, a griffon's paws and a fish for a

tail” 169 – this type of representation is unique to our manuscript, it cannot be found

anywhere else. Next to it we see a man digging the soil as the labour of the

month of Tammuz 170

– while the representation of

Scorpion as a tortoise should not

surprise us, because an illuminator living in the vicinity of Lake Constance at

the beginning of the 14th century may not have had the faintest idea what a real

scorpion looked like – the labour of the month of Marheshwan is the vine

harvest. 171

It may be noted in this context that the representation of Scorpion as a

tortoise among the signs of the Zodiac was common in contemporary Christian art,

too. 172

The combined sign of Aquarius and Capricorn radiates a certain rustic atmosphere

with the beautiful sweep (draw-well) and the kid quenching its thirst from the

bucket. Next to it we see in two medallions a sower and a peasant

“holding up a boot while warming his bare foot by the fire, above which hangs a

cauldron.” 173

The figure of a man warming himself by the fire was a widespread motif in the

representation of the winter months (December, January). 174

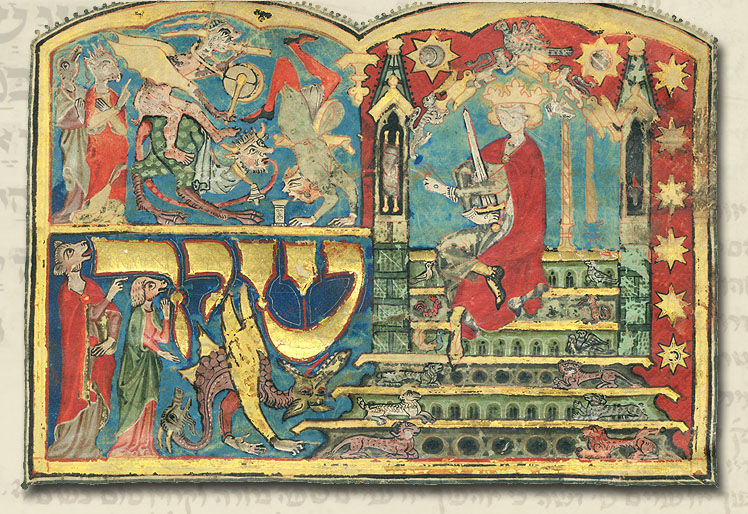

In perhaps the most famous illustration of the whole manuscript, decorating the frontispiece to the Song of Songs, we see King Solomon seated on his throne in the company of his animals with the Queen of Sheba in front of him, whom the artist has portrayed with an animal's head in the upper left-hand compartment. It seems to be no pure coincidence that Solomon and the Queen of Sheba appear together at the head of the Song of Songs: Solomon is indicated as the author in the title of the work itself, consequently the Lover can easily be identified with him, while a widespread, old tradition going back to Philon of Alexandria and eminently maintained by Isidore of Seville among others identifies the Beloved, the Bride, with the Queen of Sheba. This tradition enjoyed considerable popularity in the Middle Ages. 175

160

Sed-Rajna 1983. 32-37, esp.

32-33. Gerlinde Strohmaier-Wiederanders: Imagines anni. Monatsbilder. Von

der Antike bis zur Romantik. Halle 1999. This latter work deals

extensively and exhaustively with the characteristic representations of

the labours of the months appearing in the medallions accompanying the

signs of the Zodiac. Cf. also Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie

1968-1976. III. 274-279.

161

Strohmaier-Wiederanders

1999. 46.

162 See

Sed-Rajna 1983. 34

163

Müller – von Schlosser:

Bilderhaggaden 1898. 117. Narkiss

– Sed-Rajna 1988. Tripartite Mahzor, vol. I. Card No. 13.

164 Loc. cit. See also

Sed-Rajna 1983. 34.

165 Gotthard

Strohmaier: Arabische

Astrologie auf dem Zehdenicker Altartuch. In: Jahrbuch des

Märkischen Museums IV. Berlin 1978. 105-108, 204 (Abb. 31).

165 Gotthard

Strohmaier: Arabische

Astrologie auf dem Zehdenicker Altartuch. In: Jahrbuch des

Märkischen Museums IV. Berlin 1978. 105-108, 204 (Abb. 31).

166

Müller – von Schlosser:

Bilderhaggaden 1898. 117. Narkiss

– Sed-Rajna 1988. Tripartite Mahzor, vol. I. Card Nos 13-15.

167 See

Strohmaier-Wiederanders 1999. 33,

40, 47, 50, 59, 69.

168

Sed-Rajna 1983. 37.

169 Narkiss

– Sed-Rajna 1988. Tripartite Mahzor, vol. I. Card No. 16.

170

Müller – von Schlosser:

Bilderhaggaden 1898. 117-118. Narkiss

– Sed-Rajna 1988. Tripartite Mahzor, vol. I. Card Nos 16-17.

171

Müller – von Schlosser:

Bilderhaggaden 1898. 118. Narkiss

– Sed-Rajna 1988. Tripartite Mahzor, vol. I. Card Nos 24-25.

172

Sed-Rajna 1983. 34.

173 Narkiss

– Sed-Rajna 1988. Tripartite Mahzor, vol. I. Cards Nos 28-30. Cf.

Müller – von Schlosser:

Bilderhaggaden 1898. 118.

174

Strohmaier-Wiederanders 1999. 39,

59, 64, 68, 72, 74 (with a cauldron above the fire),

78.

175

Chastel 1949. 101.

Id.: Fables, formes,

figures. Paris 1978. I. 90-91. Cf. also Edward

Ullendorff: Ethiopia and

the Bible.

London 1968. 131-145. Giovanni

Canova: Thaclabī.

Storia di Bilqīs, regina di Saba. Venezia 2000. 2-54, 101-108. Aviva

Klein-Franke: Die Königin von Saba in der jüdischen

Überlieferung. In: Die Königin von Saba. Kunst, Legende und

Archäologie zwischen Morgenland und Abendland. Herausgegeben von

Werner Daum. Stuttgart – Zürich 1988. 105–110. André

Chastel:

Regina Sibilla. Ibid. 117-120.

Thaclabī’s

version of the story of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba from his Qisas

al-anbiyâ’ can be consulted in Chrestomathie aus arabischen

Prosaschriftstellern. Ed. by Rudolf Brünnow. (Porta Linguarum

Orientalium, Pars XVI). Berlin–London–New York 1895. 1-22. A remarkable independent development of the

story of the Queen of Sheba can be found in the Legenda Aurea,

where the Queen and Solomon at one point get involved with a piece of

wood out of which the cross of Jesus Christ will be hewn later on, a

fact of course not concealed from the Queen. J.

De Voragine: Die Legenda

aurea aus dem Lat. übersetzt von Richard Benz. Berlin 1963.

378-379.

London 1968. 131-145. Giovanni

Canova: Thaclabī.

Storia di Bilqīs, regina di Saba. Venezia 2000. 2-54, 101-108. Aviva

Klein-Franke: Die Königin von Saba in der jüdischen

Überlieferung. In: Die Königin von Saba. Kunst, Legende und

Archäologie zwischen Morgenland und Abendland. Herausgegeben von

Werner Daum. Stuttgart – Zürich 1988. 105–110. André

Chastel:

Regina Sibilla. Ibid. 117-120.

Thaclabī’s

version of the story of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba from his Qisas

al-anbiyâ’ can be consulted in Chrestomathie aus arabischen

Prosaschriftstellern. Ed. by Rudolf Brünnow. (Porta Linguarum

Orientalium, Pars XVI). Berlin–London–New York 1895. 1-22. A remarkable independent development of the

story of the Queen of Sheba can be found in the Legenda Aurea,

where the Queen and Solomon at one point get involved with a piece of

wood out of which the cross of Jesus Christ will be hewn later on, a

fact of course not concealed from the Queen. J.

De Voragine: Die Legenda

aurea aus dem Lat. übersetzt von Richard Benz. Berlin 1963.

378-379.

176 Narkiss

– Sed-Rajna 1988. Tripartite Mahzor, vol. I. No. 37.

177

Réau 1955-1959. II. I. 289.

Sed-Rajna 1987. 126.

Earlier the identification of the two female figures in the lower left

compartment was not unambiguous: from their gestures

Narkiss concluded that we

might have Solomon's judgement before our eyes.

Narkiss 1967-1968. 133. Cf.

the corresponding scene in the so-called Second Nürnberg Haggadah (fol.

40v), which leaves no doubt as to its interpretation.

Müller – von Schlosser:

Bilderhaggaden 1898. 169-170 [Fol.

40'], Tafel

XXVI. Narkiss – Sed-Rajna

1981. Card No. 164. It may be remarked that in Jewish mysticism, the

Qabbalah, the Queen of Sheba is sometimes identified with Lilith, who in

turn is sometimes regarded as identical with one of the two females

requesting Solomon's decision. Gershom

Scholem: Lilith und die

Königin von Saba. In: Die Königin von Saba 1988. 165.

178

Müller – von Schlosser:

Bilderhaggaden 1898. 119. Sed-Rajna 1983. 29-30. Narkiss – Sed-Rajna 1988. Tripartite Mahzor, vol. I. Cards Nos

34-38. The representation mainly follows the Targum Sheni to Esther

based on 1 Kings 10:18-21.

Sed-Rajna 1987. 126-127, 130 [fig. No.

148]. On the symbolic interpretation of Solomon's throne see

Réau 1955-1959. II. I.

293-294. Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie 1968-1976. IV.

21-22. King Solomon's seal. Ed. Rachel Milstein. Jerusalem [c.

1995]. 20-28, 183-182 [!].On Solomon's throne in the Islamic tradition

see Priscilla Soucek: Solomon's throne/Solomon's bath: model or

metaphor? In: Ars Orientalis 23 (1993) 113-114.

179 Ibid. 127. Cf. ibid. 155-156.

For another remarkable representation of Solomon's throne see Mathias

Köhler: Bebenhausen.

Klosteranlage und Schloß. (Führer. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.)

Heidelberg [c. 2000]. 30.

180

Sed-Rajna 1983. 29-30.

The Queen, wearing a crown, appears in the company of another zoocephalic

female and “three human-headed hybrid acrobat-musicians playing a pipe and a

tambourine and ringing a bell.” 176

In the lower left-hand compartment we see Solomon's judgement (1 Kings 3:16-28)

– according to a popular tradition the Queen of Sheba assisted at the judgement. 177

The King, wearing gloves, a purple mantle and a crown on his head, and holding a

sword, is sitting cross-legged pointing to the Torah, which is in the right-hand

turret of his throne, while in the left-hand turret there is a lamp – the

eternal light. Behind him two columns of his Temple can be seen. He is encircled

by the Sun, the Moon and the stars. On the steps of his throne sit various

animals. 178

There is only one known parallel in the synagogue at Dura Europos to this most

unique representation, but the difference of nearly eleven centuries between the

two is likely to preclude any direct connection and we must conclude that the

two artists created similar works on the basis of the same text. At the same

time we cannot completely discount the idea that in mediaeval Jewry there

perhaps existed a tradition of the transmission of pictorial representations

going back to Antiquity and still active in the Middle Ages. 179

This representation of Solomon is remarkable because it unites in one

composition, without chronological order, all the main feats of Solomon's

career: the completion of the Temple, the judgement, to which he owes his

reputation of the wise king, and the adoration of the Queen of the South, which

mirrors the universal radiation of his reign. The stars, the Sun and the Moon

echo medieval legends perhaps which attribute cosmic power to Solomon. 180

The Queen, wearing a crown, appears in the company of another zoocephalic

female and “three human-headed hybrid acrobat-musicians playing a pipe and a

tambourine and ringing a bell.” 176

In the lower left-hand compartment we see Solomon's judgement (1 Kings 3:16-28)

– according to a popular tradition the Queen of Sheba assisted at the judgement. 177

The King, wearing gloves, a purple mantle and a crown on his head, and holding a

sword, is sitting cross-legged pointing to the Torah, which is in the right-hand

turret of his throne, while in the left-hand turret there is a lamp – the

eternal light. Behind him two columns of his Temple can be seen. He is encircled

by the Sun, the Moon and the stars. On the steps of his throne sit various

animals. 178

There is only one known parallel in the synagogue at Dura Europos to this most

unique representation, but the difference of nearly eleven centuries between the

two is likely to preclude any direct connection and we must conclude that the

two artists created similar works on the basis of the same text. At the same

time we cannot completely discount the idea that in mediaeval Jewry there

perhaps existed a tradition of the transmission of pictorial representations

going back to Antiquity and still active in the Middle Ages. 179

This representation of Solomon is remarkable because it unites in one

composition, without chronological order, all the main feats of Solomon's

career: the completion of the Temple, the judgement, to which he owes his

reputation of the wise king, and the adoration of the Queen of the South, which

mirrors the universal radiation of his reign. The stars, the Sun and the Moon

echo medieval legends perhaps which attribute cosmic power to Solomon. 180